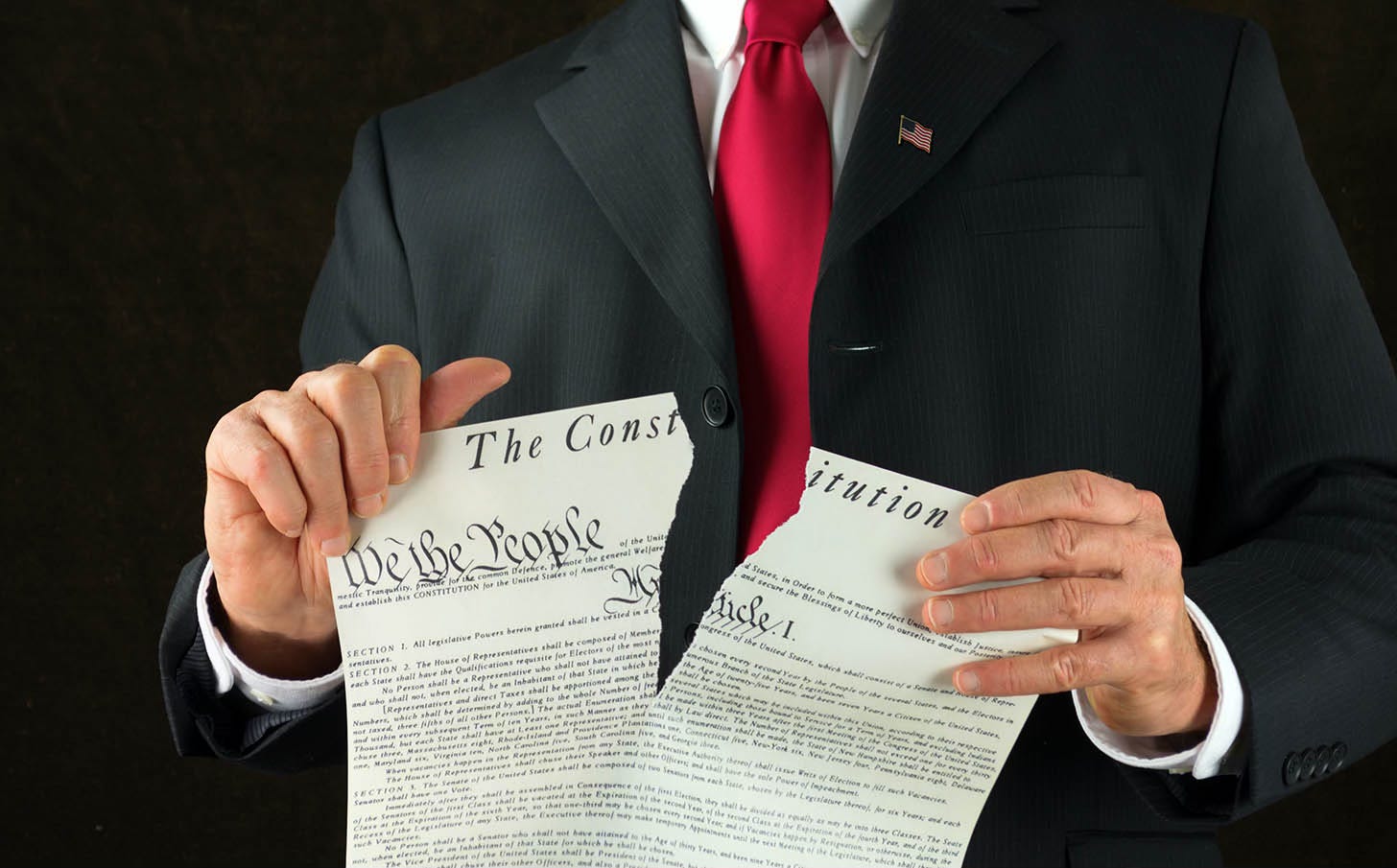

Is it Time for a New US Constitution?

The US Constitution, adopted in 1788, was the world’s first written national constitution. (Though three US states had adopted written constitutions by then.) Ancient democracies in Greece and Rome were based on laws, with no overarching constitutional document, and the English constitution is still unwritten.

The USA has changed a lot in the last 237 years. Many of our modern problems couldn’t have been anticipated during the Constitutional Convention held in Philadelphia in 1787. Ours is also a very succinct constitution, with many sub-issues left to interpretation by the US Supreme Court. Some of those interpretations are not in line with the desires of the majority of Americans.

Maybe a constitution cannot last 237 years. Maybe it’s time for us to rethink and redraft the US Constitution. Since the French revolution, which started around 1789, France has had 14 constitutions, the latest adopted in 1958.

I’d advocate for some key changes, most of them supported by a public-opinion majority in the US:

Right to abortion;

Overturning Citizens United case, which holds that the spending of money is a type of free speech protected by the First Amendment;

Deletion of the Second Amendment, so that Congress and the states can freely legislate firearms restrictions;

Elimination of the electoral college - election of US President by popular vote;

Further limitations on the power of the Presidency;

Cure for undemocratic nature of Senate, where states with small populations have as much power as those with large populations; and

Right to a clean and healthy environment.

Conservatives have their own list, which includes:

Balanced budget for federal government;

Term limits for Congress and other federal officials;

Prohibition of adding more justices to the US Supreme Court;

Further restricting Congress’ enumerated powers so that it no longer has authority over civil rights;

Congressional supermajority required to raise taxes;

Restrictions on federal ownership of public lands.

When looking at the two lists, there don’t seem to be many opportunities for logrolling, where each side gives up something that matters less to them in exchange for something that matters more. In most cases, the changes that each side wants will be opposed vehemently by the other side.

How did we get into this pickle?

The Mormons and many US evangelicals believe the US Constitution was divinely inspired. This suggests that it shouldn’t be changed: would we amend the Ten Commandments or the New Testament to help them keep up with the times? Such superstitions shouldn’t affect our national policies.

There’s no question the US Constitution is a fine piece of work. It was hammered out over the course five months in the summer of 1787 by 55 delegates from 12 of the 13 states in existence at the time. (Rhode Island did not send delegates.) The states had many competing interests, yet they managed to cooperate and compromise enough to reach an agreement. It’s hard to imagine this happening at a constitutional convention we might hold today.

The delegates to the constitutional convention deliberately made the Constitution difficult to amend, and probably didn’t realize the consequences at the time.

How could we amend the Constitution?

According to Jill Lepore’s excellent article on constitutional amendment and originalism in The Atlantic, the US Constitution has been formally amended 27 times since 1787, even though 12,000 amendments have been formally introduced on the floor of Congress.

Article V of the Constitution sets forth the ways in which it can be amended:

By a two-thirds vote of both houses of Congress, with the approval of three-quarters of the state legislatures;

By a Constitutional Convention, called by Congress upon the application of two-thirds of state legislatures.

In either case, the amendments must be ratified by three-quarters of the state legislatures.

It seems unlikely, in the current political climate, that substantial amendments to the US Constitution will be agreed upon by two-thirds of the Representatives and Senators in Congress.

A constitutional convention would be very risky for both sides. Article V contains no rules or limitations for the convention. Would each state get a fixed number of votes (as in the Senate), or would each state’s number of votes be based on the state’s population, as in the House Of Representatives?

Could the scope of amendments adopted in such a convention be limited somehow? The text of Article V provides no support for such limitations, but a petition proposed by the conservatives, and already ratified by 18 states, purports to restrict the convention to “proposing amendments that will impose fiscal restraints on the federal government, limit its power and jurisdiction and impose term limits on its officials and members of Congress.” If Congress were to call the convention, would such a limitation by Congress be upheld by the Supreme Court? I think it would depend on the political climate at the time.

How do we adapt the Constitution if we can’t amend it?

Since the Constitution can’t be amended, at least for now, we rely on judicial interpretation, mostly from the US Supreme Court, to adapt it to current conditions. The Constitution’s text is quite telegraphic, so the Court has a lot of room for interpretation. For example, the Court has added rights that are not called out in the text of the Constitution, such as the right to privacy, and the right to abortion. These rights were added by the Warren and Burger courts: privacy in Griswold v. Connecticut in 1965, and abortion by Roe v. Wade in 1973. Those who opposed those rights considered these decisions to be judicial activism, legislation from the bench, and beyond the scope of what the courts should do.

In 1971, Yale law professor Robert Bork advanced a new theory of constitutional interpretation that came to be called “originalism.” His nomination to the US Supreme Court failed, but his idea was taken up with a vengeance by Antonin Scalia, who came onto the court in 1986.

When interpreting statutes, the touchstone is, at least theoretically, the intent of the legislators at the time the statute was adopted. In practice, inquiries into the meaning of statutes rarely consider what the legislators were subjectively thinking when they adopted the statute because the statute’s plain meaning, if it’s not ambiguous, determines the interpretation. Even if the statute is ambiguous, there are many interpretative tools that can be used before trying to intuit what was in the mind of the legislators adopting the statute.

Originalism applies this method to the Constitution: it means what the delegates to the 1787 Constitutional Convention meant it to mean at the time they signed the Constitution. There are a number of problems with applying this practice to the Constitution:

The world has changed a lot since 1787. The founders would have been horrified at the idea of legalized abortion, for example, but a majority of the US supports it now. The US was primarily an agrarian economy in 1787, but we have moved forward. For a while we were primarily a manufacturing economy, but no longer; we’re primarily a service economy now. Slavery is gone. We mostly live in cities, while most people in the US in 1787 did not. Many modern problems were not present in 1787.

The intent of the framers can be hard to determine, and different framers may have had conflicting intentions. The historical record can be skimpy, contradictory, or non-existent on some issues.

If a court mis-interprets a statute in a way that offends the legislature that adopted it, the legislature can amend the statute. This happens fairly frequent in the statutory realm, but, as discussed above, is impractical for the US Constitution.

We need an amendment to the Constitution specifying how the Constitution is to be interpreted. I would propose that it require courts to follow the spirit of the Constitution while taking into account current conditions that may have changed since the text was adopted. This is the type of interpretation used by the Warren and Burger courts before originalism appeared on the scene. Supporters of originalism argue that such standards turn constitutional interpretation into legislation from the bench. But the alternative is to tether our interpretations of this country’s most important legal document to questionable interpretations of 18th-century history.

The current Supreme Court is very accommodating to the Trump administration, having granted many more emergency requests than past courts would have. Originalism gives the Court an additional set of interpretive tools it can use to come to the result it wants to. Justices Thomas, Gorsuch, and Barrett are avowed originalists, and justices Alito and Kavanaugh sometimes use originalist arguments. They employ originalism mostly to achieve outcomes favorable to Republican and conservative causes.

Republicans are trying to hold the line on social changes to the US. They want to revert to an imagined happy time when the dominant class was straight Christian white males. This will be a losing fight in the long term as demographic and social trends are against them. But they won’t go down quietly. The Trump administration doesn’t mind eroding political norms that have served us well for decades, taking actions that are clearly illegal, using the power of the federal government to pursue Trump’s political and business enemies, imposing what amounts to martial law to quell freedom of expression, changing voting rules to exclude those who might vote against them, and so on. These are stopgap measures, that won’t hold back the tide forever, but they are damaging the legal, political, and moral fabric of this country, contributing to its decline.

The situation is similar to climate change. We can hold back on taking action to mitigate it, but, as long as we keep emitting greenhouse gases, climate impacts, in the form of increased heat waves, rainstorms, hurricanes, drought, sea-level rise, and species loss, will keep increasing every year. The economic costs are already huge, as are the impacts to people’s lives. It will gradually get much worse, and when the impacts get bad enough we’ll take strong action. When we do, it will cost us a few percent of our GDP, but the US, and the larger world, are currently prioritizing short-term economics over long-term damages. A recent New Yorker cartoon summed up the situation pretty well. Cavemen sitting around a fire said “we destroyed the world, but, for a time, we provided significant value for our shareholders.”

The US is the second-largest emitter of greenhouse gases, after China. Our per-capita emissions are much higher than China’s. China is taking the leadership on climate through its electrification campaigns. A strong majority of Americans think we should be doing more to fight climate change. If the US had the constitution that it deserves, a constitution that accords better with modern times and the needs and wants of our citizens and other residents, we could be responding more effectively to the most important problem of our time.