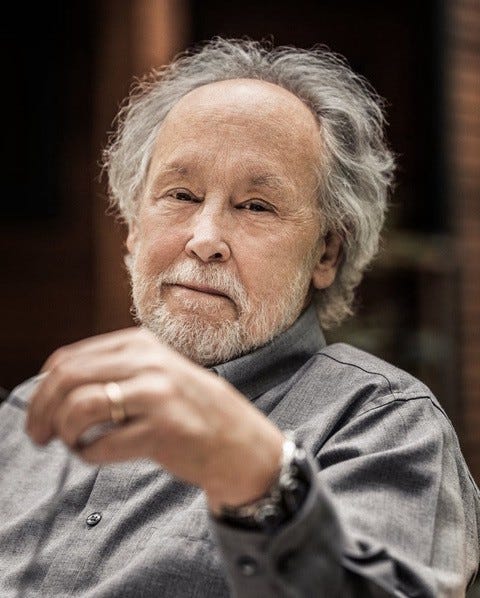

Barry Lopez — an Appreciation

Barry Lopez, one of the great nature writers of our time, passed away on Christmas, 2020, at the age of 75. His greatest book was Arctic…

Barry Lopez, one of the great nature writers of our time, passed away on Christmas, 2020, at the age of 75. His greatest book was Arctic Dreams, published in 1986, and winner of the National Book Award. His last book, Horizon, published in 2019, was also an important book, with roughly the same scale and schema. The books are organized by geography: many chapters focuses on a place and often, in Arctic Dreams, on a type of animal.

Arctic Dreams is my favorite non-fiction book. It evokes a sublimely beautiful but strange world teeming with life, relatively inaccessible at the top of our planet. Ever since I read the book thirty years ago, I’ve wanted to go see the Arctic. But I haven’t managed to travel there. It’s hard to get to the far north; there are few commercial flights to Baffin Island or Ellesmere Island. Svalbard, a Norwegian island just as far north, can be reached by a series of flights, at a reasonable cost. But getting to Iqaluit, for example, capital of the Nunavut Province of Canada, is expensive.

And seeing the Arctic backcountry is dangerous. I’ve been an avid hiker for over thirty years, and have led numerous Sierra Club local hikes and backpacks in the Sierras. I’m confident hiking by myself in the lower 48 in summer or winter. But the dangers in the Arctic are different, and I wouldn’t hike there without a guide. Grizzly bears and other wild animals can kill you, so you have to carry a rifle and know how — and be willing — to use it. It’s very cold much of the time. And the changing conditions of ice, snow, and water can kill you in a variety of ways. It is a very dangerous environment for those not trained to live in it.

Of Wolves and Men

Lopez seems to have travelled the Arctic mostly with groups of scientists doing research. He also spent time hunting and working with Eskimos and other natives. He seems to have developed his methodology, and his philosophical outlook, while researching and writing Of Wolves and Men. That book came out when Lopez was just 33 years old, eight years before Arctic Dreams. It’s a great book and was a National Book Award finalist.

For the wolf book, Lopez spent hundreds of hours watching wolves in the far north (where most of them live now, since we’ve hunted them to near extinction in the lower 48), alone, and in the company of wolf biologists and Inuit hunters. In his view, the hunters understand wolves the best, because the wolves make a living the same way the hunters do: by knowing and carefully observing the landscape and the plants an animals in it. Eskimos do not eat wolves, for the most part, but observing their behavior can provide vital clues to the location of animals the wolves and men both eat, such as caribou. The wolves usually know where the caribou are, or are likely to be.

_Of Wolves and Men_’s first half explains the wolf. The second half deals with the relationship between wolves and humans. Indigenous people know wolves best, in an anecdotal sort of way, though scientists tend to ignore their knowledge. Indigens, as hunter-gatherers, see themselves as part of the animal kingdom, intimately related to the landscape. Non-indigens see themselves as separate, outside. For the former, the land is the universe they inhabit for the latter, the wild landscape is to be dominated, controlled, adapted to human use.

A chapter titled “The Beast of Waste and Desolation” recounts the systematic killing of almost all the wolves in the lower 48 states — hundreds of thousands of them — and the underlying attitudes. Why were wolves hated so much in 19th-century America? It was partly due to the frontier mentality–the idea that the wilderness was savage, pagan, dark and evil and needed to be tamed and domesticated. Wolves were part of the wild and preyed on sheep and cattle, so they had to go. I can understand that ranchers had a strong economic incentive to reduce their livestock losses, but the antipathy towards wolves went way beyond that. Duty, manhood, civilization, sport, and conquest of evil were all cited as justification for wolf killing. And the fun of shooting dozens of them from an airplane in a day.

The book’s final section considers the history of Western attitudes toward the wolf, and wolf literature and mythology, going back to the Middle Ages, when the wolf was seen as a companion to both saints and the Devil, and a symbol of mankind’s inherent bestial nature. “Throughout history man has externalized his bestial nature, finding a scapegoat upon which he could heap his sins and whose sacrificial death would be his atonement. He has put his sins of greed, lust, and deception on the wolf and put the wolf to death — in literature, in folklore, and in real life.” Werewolves were taken seriously in the Middle Ages, representing all that was base in human nature. The Inquisition burned those suspected of werewolfry at the stake.

Arctic Dreams

After an introductory chapter, the first three chapters of Arctic Dreams each focus on a place and an exotic Arctic beast: the muskox on Banks Island, the polar bear on the sea ice north of Alaska, and the narwhal in Lancaster Sound. It would be worthwhile traveling to the Arctic just to see these amazing animals. Many other more-common types of wildlife, like wolves, caribou, Arctic foxes, and birds, are considered in other chapters. One reason I want to go to the Arctic is to see the extraordinary wildlife.

The next chapter is about migration. Because of the extreme winters in the north, many species migrate out for the winter. Millions of snow geese, for example, fly more than 3,000 miles from their Arctic breeding grounds to wintering grounds in the U.S. and Mexico. They spend about half their year migrating to and fro. Arctic terns migrate 44,000 miles round-trip to the Antarctic. Caribou, walrus, and whales also migrate significant distances annually. Lopez “came to think of the migrations as breath, as the land breathing. In spring a great inhalation of light and animals. The long-bated breach of summer. And an exhalation that propelled them all south in the fall.”

The migration chapter also discusses the first coming into the Americas of humans, via the Arctic. I suspect that the science on this issue has changed in the 35 years since Arctic Dreams was published. But the basics remain the same: Asians crossed the Bering land bridge during the Wisconsin glaciation, between 30,000 and 11,000 years ago when sea levels were around 100 meters lower than they are now. The Dorset culture that existed between 500 BCE and somewhere between 1000 and 1500 CE is mysterious. Their masterly miniature ivory and bone carvings are dark and unsettling. The Thule culture, which came after the Dorset, spread from Alaska east to Greenland between 1100 and about1400 CE. The Thule people were accomplished hunters of bowhead whales and other animals. They are the ancestors of the present-day Inuit ( Eskimos), who adapted to the cooling that started around 1100 CE. All of these people were hunter-gatherers, feeding themselves mostly by hunting.

My favorite Arctic Dreams chapter is the one entitled “Ice and Light.” I want to see the grand Arctic icebergs even more than I want to see the Arctic wildlife. Lopez felt something similar: “If I had a desire simply to be with anything in the North, it was to be with icebergs. I do not know if I had had this wish for years or if it only intensified as the prospect of the voyage loomed. But when I saw them, it was as though I had been waiting quietly for a very long time, as if for an audience with the Dalai Lama.” He describes in scientific, but fairly ecstatic terms, the varieties of types of ice floating in the Arctic: sea ice, freshwater ice, grease ice, nilas (an elastic layer of ice crystals about an inch thick), gray ice (young sea ice), ice islands up to 300 square miles in size, which scientific expeditions can camp on for decades, and tabular icebergs up to 50 cubic miles in volume, the largest objects afloat in the Northern Hemisphere.

Even relatively flat ice has a lot of configurations, which are always changing, adding to the dangers of traveling on the ice. There are pressure ridges that can be difficult to cross, and the network of leads — open water between expanses of sea ice — is changing all the time, under the influence of winds and currents. Walking on the ice, it’s easy to get trapped when an adjacent lead opens up. It’s dangerous for ships, too. The moving ice can crush ships and boats traveling in the leads. Ships can get frozen in place for the winter if they aren’t careful. But there are large areas that stay open all winter amidst the ice, called polynyas. They can harbor huge numbers of overwintering seabirds and marine mammals.

There’s something transcendent about all this ice. In _Magic Mountain_’s “Snow” chapter, the everyman protagonist, Hans Castorp, reaches the pinnacle of awareness in an ecstatic vision during a whiteout, as he almost freezes to death in a snowstorm. Lopez likens icebergs to gothic cathedrals, based on their shared “architecture of light,” and the mystical experiences they engender. I hope for an Arctic voyage someday to spend transcendent time amid icebergs and nilas and sea ice.

The rest of “Ice and Light” talks about light in the Arctic. With constant night in the winter and the sun circling around the horizon but never setting during the summer, there are all manner of exotic optical effects: mirages, solar arcs and halos, and, of course, the aurora borealis. Another set of spiritual experiences I can hope to have when I visit the Arctic.

The next chapter, “The Country of the Mind,” is about attitudes toward the land. For the Inuit, hunting is a spiritual exercise, and the goal is to become one with the land. For them, the land is everything. It includes plants and animals in a unified whole. It is much more than just a place to live. It is their source for food and tools. And their mythology and spiritual practices are based on the land. A spiritual landscape exists within the physical landscape. “The land is like poetry: it is inexplicably coherent, it is transcendent in its meaning, and it has the power to elevate a consideration of human life.” Westerners, coming into the Arctic, see the land in much more instrumental and utilitarian terms. For them, it is mostly a repository of natural resources to be exploited for profit.

The remaining chapters of Arctic Dreams mostly recount the history of European exploration in the Arctic. Europeans were interested in the Arctic as a possible route to China, but it took hundreds of years of exploration to find the Northwest Passage. The first complete passage by ship wasn’t made until 1903, about four hundred years after the English started exploring the Arctic for a way through to China.

The other principal European interest in the Arctic was resource extraction. Whales were killed for their blubber, which could be rendered into whale oil, to light lamps. Whalebone (baleen) was used to make umbrella staves and Venetian blinds, portable sheep pens, window gratings and furniture springing. Seals and cod were also commercially important. But the biggest fortunes were made from furs. In 1670 the Hudson Bay Company was essentially given sovereignty to all lands drained by rivers emptying into Hudson Bay — a huge territory. A century later, its main business became the fur trade. In the century beginning in 1769 it sold at auction in London 891,091 fox, 1,052,051 lynx, 68,694 wolverine, 288,016 bear, 467,549 wolf, 1,507,240 mink, 94,326 swan, 275,032 badger, 4,708,702 beaver, and 1,240,511 marten furs.

Europeans saw the new world as an essentially unlimited source of resources they could expropriate for profit. Annie Proulx’s wonderful 2016 novel, Barkskins, recounts three hundred years of exploitation of the New World’s timber and fur. The resources were there for anyone to take, and take they did. The characters in Barkskins exclaim repeatedly that the forests are so huge as to be inexhaustible, but, of course, they were eventually cut down. We still have the attitude, at least in some quarters, that resources on public lands should be available for private exploitation with little or no compensation to the public. Ranchers in the western U.S. pay very little for the right of their cattle to graze and destroy ecosystems on federal land. Loggers pay way below market value to cut timber in our national forests. Oil and gas companies pay very little to extract fossil fuels. Oil and gas appears to be the resource that nation-states and oil companies are currently fighting over in the Arctic, even though, to deal with climate change, we must stop burning fossil fuels within a few decades. I’m sure Lopez would agree that it would be short-sighted to despoil rare and beautiful Arctic landscapes for oil and gas production that will never be allowed.

Horizon

Lopez organizes his last book, Horizon, like the first chapters of Arctic Dreams: each chapter after the first introductory one deals with a trip to a specific place, most likely a place where he’s already been, where Lopez works with a group of people. In the introduction he sums up his mission: “I wanted to see and write about landscapes I thought I could have an informing conversation with, and about the compelling otherness of wild animals.” His other focus is on indigenous people, hunter-gatherers, who have relationships with the landscape similar to those of wild animals. This trio of landscape, animals, and indigens, provides Lopez’ moral map. Lopez explains the title in terms that are easily translated into metaphor: “When a boundary in the known world — say, a geographical one for Thule people migrating eastward from Alaska, moving farther into an inhospitable world than anyone had ever gone — becomes instead a beckoning horizon, the leading edge of a farther destination, then a world one has never known becomes an integral part of one’s new universe.”

The first chapter recounts Lopez witnessing a storm at Cape Foulweather in Oregon, a couple hundred miles from his home. He is drawn to the site because it’s where the explorer James Cook made his first landfall on the west coast of North America. Lopez recounts visiting several Cook-related sites, such as Botany Bay in Australia and Point Venus in Tahiti. The chapter is all about exploration — through telescopes, undersea, and by closely observing the landscape. It’s also about explorers’ and immigrants’ interactions with native peoples, one of Lopez’ most prevalent themes. He alternates descriptions of the storm and the setting from which he is observing it with ruminations on exploration and the interaction of cultures. It’s a meditation, searching for transcendence in the storm while trying to understand what happened in that particular place.

The next chapter recounts Lopez’ return to the Arctic — Skraeling Island — a few years after completing Arctic Dreams. He walks around observing the landscape and works with a team excavating Dorset and Thule sites. The beauty and strangeness of the Arctic come alive in this chapter, which is especially poignant because the Arctic, more than any other place on Earth, is being radically affected by climate change. The average temperature in the Arctic has increased 2.3˚C — about twice as much as the planetary average — since 1970.

Lopez moves next to the Galápagos Islands, which have an astonishing range of endemic species. They partly inspired Darwin’s theory of evolution. It’s a big tourist site because of the unusual animals. The government of Ecuador preserves 97% of the islands’ land as a park, but there are enduring conflicts between the local residents, many of whom are poor and live by hunting and fishing, and the park service, whose mission is to preserve the park in as close to a natural state as possible. There are a lot of feral dogs, pigs, and goats, as well as invasive plant species, but it’s difficult to come to an agreement on which species should be removed and which “natural state” would be best. Lopez describes a number of intense animal encounters there. He ends the chapter with a discussion of Darwin’s theory, lamenting that humans’ lack of care for the environment will result in genetic harm to them. But he doesn’t take into account that natural selection has mostly stopped for humans, because, once we’re born, we pretty much all survive, even the unfit.

In the following chapters, Lopez works with Africans in Kenya surveying for early human fossils; he wanders around Australia visiting mining sites, indigenous people, and former penal colonies; and he is part of a team searching for meteorites in Antarctica.

Morality

Lopez brings ethics into practically every page of his writing, though he does it gently. A common thread throughout his books is the European invasion of the Americas, and the attendant horrors: the killing of around 90% of the native human population, some 20 million people; a similar holocaust of wildlife, killed for fur, oil, meat, and other uses; heavy extraction of timber and other resources that laid waste to millions of acres of wilderness. He recounts in passing countless instances of casual cruelty, such as the shooting of a pair of polar bear cubs from a ship in the Arctic, just for fun, to see how the mother bear would react.

The indigenous peoples were hunter-gatherers and the incoming Europeans were from agricultural/industrial societies. This invasion caused a clash of cultural systems, which the invaders were bound to win. There is a thread running below the surface of much of Lopez’ writing: a nostalgia for the hunter-gatherer life. Numerous writers such as Yuval Noah Harari have suggested that hunter-gatherers had a better life than we do. They had more leisure, more variety in their days, much closer contact with landscapes and nature. Even so, we can’t go back, largely because the human population has grown so large it greatly exceeds the carrying capacity of the planet’s land, for hunter-gatherers.

He mourns how resource extraction hurts locals: “The seductive power of this system of exploitation — tearing things out of the earth, sneering at the least objection, as though it were hopelessly unenlightened, characterizing other people as vermin in the struggle for market share, navigating without an ethical compass — traps people in a thousand exploited settlements in denial, in regret, in loneliness. If you empathize with the [indigenous people] over their losses, you must sympathize with every person caught up in the undertow of this nightmare, this delusion that a for-profit life is the only reasonable caring for a modern individual.”

Lopez is interested in things we can learn from landscapes. “The land retains an identity of its own, still deeper and more subtle than we can know. Our obligation toward it then becomes simple: to approach with an uncalculating mind, with an attitude of regard. To try to sense the range and variety of its expression — its weather and colors and animals. To intend from the beginning to preserve some of the mystery within it as a kind of wisdom to be experienced, not questioned. And to be alert for its openings, for that moment when something sacred reveals itself within the mundane, and you know the land knows you are there.” This relationship of an individual to the landscape is built into our human genome. For hundreds of thousands of years before we invented agriculture we lived off the land; that’s what we evolved to do. There is a primal satisfaction in walking through the pristine landscape.

Indigens are conduits for landscape knowledge because they are so strongly rooted in the land. We are still encroaching on the few remaining pristine wilderness landscapes left, e.g. by proposing to extract oil in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. And we are reducing the scope of indigenous lives in those landscapes, through regulation and continuing assimilation. We could certainly do more to protect landscapes, as the recent push to preserve 30% of the land by 2030 suggests. And we should strive to protect indigenous customs , languages, and ways of life, even when doing so provides few immediate practical benefits to the rest of us.

Conservation

Lopez comes from the mold that made Thoreau and Muir. They write in ecstatic terms about their excursions into “nature.” Their ethos is traditional conservation, which is out of fashion among environmentalists now. Thoreau and Muir wrote primarily for city-dwellers whose lives encompassed little natural beauty. Muir wrote mostly of the majesty of California’s Sierra Nevada mountains. Thoreau wrote primarily about the woods and streams within an afternoon’s walk from his home in Concord, Massachusetts. Their writings are implicit pleas to keep beautiful landscapes in their natural state so they can be enjoyed by those who have the time and means to visit them.

Lopez’ travels are much broader and more culturally cognizant. For me, Arctic Dreams served in part as a Thoreau/Muir-style paean to the natural beauty of the Arctic. It makes me want to go there and see it. But most of Lopez’ writings concern problems he finds at his destinations — cultural, ethical, and environmental problems. And he is much more tuned-in to the people, especially indigenous people, he finds and works with at his destinations. His plea is to preserve natural landscapes as a reservoir of primal knowledge, and as the root of the human psyche.

Thoreau and Muir are the left-side bookends, writing to inspire interest in the largely unexplored natural landscapes opening up in a young America. Lopez is the bookend on the right, mourning the demise of such landscapes world-wide.

Climate Change in the Arctic

Lopez barely mentions global heating in his books, but it’s lurking there, out of the limelight. He recounts a voyage into a strait that, a couple hundred years ago, was iced in most of the year; it was completely clear of ice when his ship passed through it. The Arctic is warming twice as fast as the rest of the world. The average temperature in the Arctic has increased by almost 4˚C (7.2˚F), a huge increase. The extent of sea ice is rapidly shrinking — it’s down by around 50% at the sea-ice minimum in September. This shrinkage is part of a positive feedback cycle — the open water that’s replacing the ice absorbs much more heat than the ice did, resulting in the loss of yet more ice.

Global heating is causing huge changes in Arctic ecosystems. Polar bears depend on sea ice for their winter hunting, so their habitat is shrinking; this is one reason why they were listed in 2008 as a threatened species under the U.S. Endangered Species Act. Temperature increases are forcing many species of plants and animals in the rest of the world to move toward the poles in search of cooler temperatures, but this is impossible in the Arctic — there’s nowhere further north for them to go. Permafrost, which underlies much Arctic soil, is thawing, and will release formerly trapped methane, a potent greenhouse gas, as it thaws. The methane will increase the amount of heat the Earth retains, leading to more permafrost thaw, another positive feedback.

In its last few months, the Trump administration rushed through the opening of oil and gas leasing in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. We don’t need the oil and gas; indeed, we have proven reserves of fossil fuels that are much larger than the quantities we can afford to burn if we intend to keep global heating below 2˚C. We should be closing, not opening, public lands in the U.S. to oil and gas drilling. It’s particularly galling that the administration should propose to invade pristine lands in the Arctic, lands with thriving but sensitive ecosystems, lands that are the most affected by global heating, with an activity that hastens the climate disaster.

Lopez is not a climate crusader, but much of his writing goes to heart of the moral and ethical choices we collectively make in connection with landscapes and the environment. Climate change is, in my opinion, the most important issue we’ve ever faced as a species, and it is, at the bottom, a moral and ethical issue. Lopez’ voice, urging us quietly but firmly to pay attention to landscapes, ecosystems, and indigenous people, is a timely reminder of our natures as animals and our strong animal connection to the planet on which we live.